Above the clouds, the sun always shines

When I was a child we holidayed mostly in the United Kingdom, with occasional camping trips to Germany via the ferry from Harwich. There’s a layby, just west of Settle, where we once stopped to fix a puncture: my dad was a very patient man, but he really wasn’t amused when I asked him if we were nearly there yet: as we had set out from Kendal only an hour before, the answer was definitely ‘no’! . All this meant that my first experience of travelling by air didn’t happen until I was in my twenties. I took off from Manchester airport on a foul, wet and overcast day, bound for Australia, and discovered for the first time that, unless it’s night, the sun always shines when you’re above the clouds. And of course, even if it’s night, the starlight from a plane is remarkable – no light pollution either. All these years later, I still find this amazing!

Losing the wonder

As adults, we tend to lose sight of wonder. Children can be captivated by things we don’t notice any more; a shiny beetle, raindrops hitting a puddle; snowflakes almost as big as paper tissues falling from the sky – we adults did a double take last week and wondered how on earth we were going to get to the bus stop or the supermarket, but the children were full of wonder – they live much of the time above the clouds, so to speak, in that land of sunshine and starlight. We adults are used to life being overcast. Most people have occasional glimpses of glory, around half of adults have had what they call a religious experience – many of these are people who don’t count themselves as religious in any way. For most of us these are fleeting encounters: things that last a moment and overwhelm us with beauty or glory or holiness: moments when our souls are stirred by beauty, or when we are overwhelmed by the inner meaning of something.

An encounter with a sparrow

Something like this happened to me last year. I was with friends, celebrating a birthday in a friend’s garden in Manchester. I was sitting near a birdfeeder. Suddenly a sparrow came down to feed and I was overwhelmed by its presence: I could sense the beauty of its soul, I could feel the whole of creation captured in its tinyness and fragility: although it was a plain little bird its beauty was stupendous. Something happened to time – this was a fleeting moment but seemed to last for eternity. My friends were all around me, chatting away and laughing, but in, this moment, it was as if someone had turned the volume down so the main thing I could hear was the sound of the bird’s wings moving through the air. And then it was gone – and everything went back to normal.

The glory is always there

The sparrow will always be beautiful, miraculous and carry eternity with itself: the glory is always there – it’s just that we don’t always see it. Occasionally eternity breaks through and our eyes are opened. I think when Peter and John and James witnessed the Transfiguration, they didn’t see a change in Jesus – they simply saw him properly for a few moments, saw him fully. From their perspective his face changed and his clothing became dazzling white. But, especially reading Luke’s Gospel, as we are doing at the moment, we the readers or listeners, know that God’s glory has always been there in Jesus. We have had Gabriel and choirs of angels to tell us. Elizabeth has told us: Simeon and Anna have told us: John the Baptist has told us, and God’s voice told us too, at Jesus’ baptism: even Peter has told us ‘You are the Messiah’. Jesus’ miracles have told us too. At the Transfiguration, I think the three disciples see what they already know – for a moment they leave their cloudy existence and take to the skies – like children, they see the glory that is always there.

We are changed

We are told that we can’t always stay on the mountain top: we can’t spend our lives gawping at glory. We have to remember the mountain top experiences and let them feed us when times are hard. Luke illustrates this well: the following day, on their return to the valley, Jesus and disciples are confronted with the worst of things – a very sick child, frantic parents and a seething, discontented crowd. We have moved from a revelation of glory to utter chaos in the space of a few sentences. You can imagine the three disciples struggling to bridge the gap between these two experiences, and probably wishing they were back up the mountain, basking in the light of Jesus’ glory. Perhaps what they had experienced helped them to cope – gave them something to hold on to.

But I think these odd experiences of glory do more than this: they are more than something to hold on to when life is tough. Because the Transfiguration witnessed by the disciples, and our own odd experiences of glory and wonder, change who we are and how we see things. These experiences are not simply something to cling on to when life is hard – a reminder that life isn’t always rubbish; rather these experiences change our very perception of life: like going up in an aeroplane, when we come to realise that the sun is always shining above the clouds, and at night there are beautiful stars. Once we have caught a glimpse of glory, once we have been overwhelmed by beauty, life itself is transfigured – we know the truth that the world is shot through with grandeur, that the eternal is contained within mortal, material things, that there is goodness and perfection all around us, even when times are dark and life is hard. At such times, then, we don’t just cling onto the beauty we once glimpsed, but we know that life is infinitely beautiful and precious, that creation reflects God’s goodness, that the most mundane things are miraculous, that God’s love is actually all around us, even though we can’t sense it.

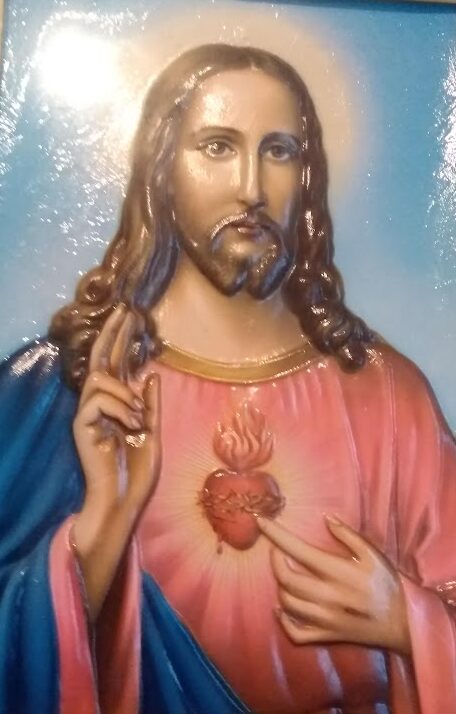

A picture of The Sacred Heart of Jesus

On Thursday, someone left a picture on the Vicarage steps, wrapped in two plastic carrier bags which smelled badly of cigarette smoke. It’s a 3d plastic picture of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. In many ways it’s hideous – it’s plastic, sentimental and Jesus is depicted a white European which is ethically dubious. I have no idea who left it there, or why – but it was a gift, so it deserved some consideration and gratitude. Having spent a few days looking at it, I have come to the conclusion that there is more to this picture than meets the eye. I looked it up, and found that this is an image with a long and honourable tradition, beginning at the time of the crusades with a devotion to Christ’s wounds – you can imagine that this would be important to wounded crusaders. It has also to do with the humanity of Jesus – a human heart beating with divine compassion. So you see, behind this 3d plastic Jesus lies something profound and beautiful. It reminds us, as does Luke, writing about the Transfiguration, that Jesus will still carry the fullness of God’s glory a few pages later, so to speak, when he is beaten, tortured and crucified. Even on the cross, that beauty is still there – the beauty of God’s beloved. The beatings, torture and crucifixion took place at the ands of those who chose not to see, or had lost the ability to see, the beauty of the divine-human before them. And evil still abounds when we choose not to see – or lose the ability to see, that the world around us shot through with God’s glory – even the grotty, difficult bits.

“When Jesus is transfigured, it is as if there is a brief glimpse of the end of all things–the world aflame with God’s light.”

Tweet