A few weeks ago, an image of The Sacred Heart of Jesus was left on the Vicarage steps, with no indication of who it was from or why they had left it there. My instinct was that this was something to which I had to give my attention, so I put it on my desk and wondered and pondered.

A few weeks after this I had cause to catch a taxi to the hospital one morning. I booked in advance from a company who got a good rating, locally, on the internet. Much to my surprise, the taxi driver told me that he had been asked by a passenger, a few weeks earlier, if he would drop a package off at the Vicarage – it was OK just to leave it on the steps. He confirmed that, yes, it was a picture of Jesus. A very strange coincidence!

At this point, I concluded that I really had to pay attention! I’m still exploring, but here are a few things which might be useful, when preaching about Thomas, who wanted to see and touch Jesus’ wounds.

First. As I mentioned on Easter Sunday, when preparing the Paschal Candle with the children, the risen Christ still carries his wounds: the paschal candle, symbol of resurrection light and life, has piercing nails or incense pins which mark the five wounds. Thomas draws our attention to this: to him, the wounds are evidence that this really is Jesus, not just someone who looks like him.

The risen and ascended Saviour still bears these wounds in Heaven. This means that human suffering, scarring and woundedness are now part of who God is; those scars are there, at the heart of the Trinity.

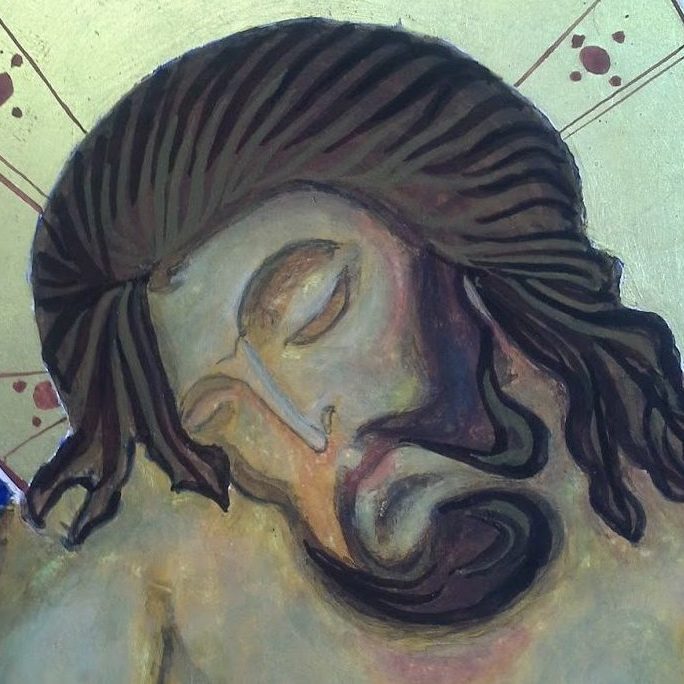

Secondly, we, like Thomas, must have the courage to look at scars and not avert our eyes. A few months ago, I was looking, with a colleague, at an icon I’d painted: a copy of the ‘Extreme Humility’ icon. He looked at me with pity and said ‘But there’s so much suffering there’: he could barely bring herself to look at the icon. Having faced a good deal of suffering myself over the past few years, he was also letting me know that he felt sorry for me, but in a way which let me know that this was something which had diminished me in their eyes – I was an object of pity, and perhaps not a true Christian.

There is a good deal of attention given, at the moment, to the idea of church ‘health’. Sometimes it is the opposite of Narnia where it was always Winter but never Christmas. Now it is always Christmas, always Easter, but never Winter, never Good Friday. There is an inability in much of contemporary Christianity (in the West, at least) to stand with Thomas and gaze on those wounds, learning to recognise that they are now part of who God is, and part of who we are: being both human and divine, wounds are places of life and growth.

In January I injured myself badly, when I fell down some steps. Two operations later, I’m still having the wound dressed twice weekly. Last week I was slightly shocked because the wound was bleeding, but the nurse was quite excited: ‘No, that’s really good: it means there’s a good blood supply, which means your body is busy healing itself. I thought, ‘there’s a sermon in that somewhere’!

Thirdly, there are fascinating images of the wounds of Christ, if you look on the internet. In the middle ages they seemed to develop a life of their own: they become separated from Jesus’ body and exist separately. This seems very odd to us: the medieval mind seems to have been richly creative and imaginative. In some images the wounds bear crowns or are decorated with jewels; in others the wounds become wells – sources of life, mercy and hope. In other images, the wounds burst to life with flowers and leaves.

I’m still pondering these images, and I have a way to go. But it does seem to me that these ‘abstracted wounds’ are things that can give us hope: the suffering of the world seems unbearable, and is hard to assimilate. And yet these wounds of Christ suggest that, even from the worst of horrors, life can spring again. But, we have to have the courage, like Thomas, to look at the wounds. A failure to look at the wounds seems to lead, inevitably, to a failure to rebuild life of individuals and the world, in healthier, kinder and stronger ways.

Look at the Kintsugi heads made by Billie Bond: images of the strength and beauty of the healing of the mind.

Tweet