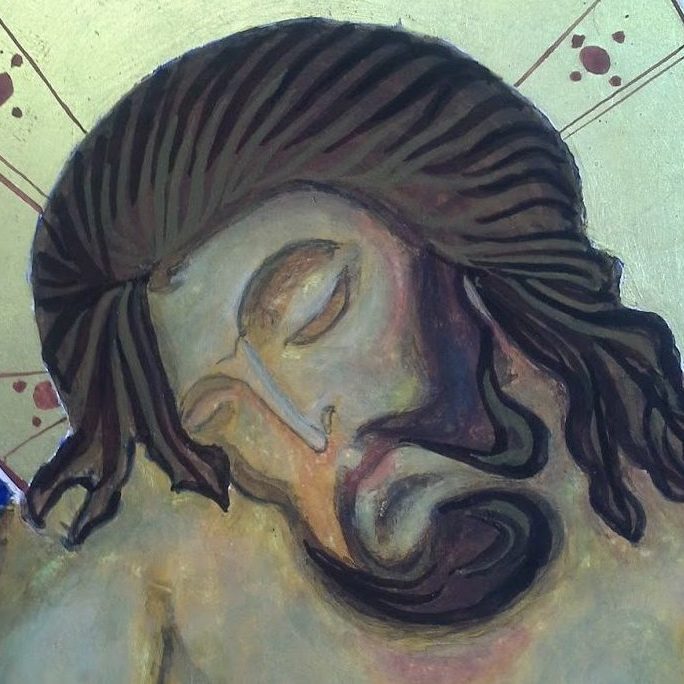

Today is Passion Sunday – the beginning of the two most holy weeks of the Christian calendar. It is, under normal circumstances, our habit at St Oswald’s to read the Passion Gospel on this Sunday rather than on Palm Sunday. Doing so is always a powerfully moving experience – Jesus moving inevitably towards crucifixion and death. There is exaltation, betrayal, humiliation, desertion, forsakenness, terrible pain, and finally that moment of release as Jesus dies and gives himself into his Father’s hands. This terrible series of events is echoed across the world even as we speak as people are tortured in prison cells, or die slow and painful deaths in places where healthcare is inadequate or non-existent. Each time I read the Passion Gospel it seems to be an account of all suffering, past and present, near to home or far away – somehow this story encompasses all pain, desertion, abandonment, pain and death.

But what does this mean, and how does it help? Does it make any difference to people who suffer or who have experienced trauma or abuse? What does it all mean to ordinary Christians? There are many ways of approaching these questions, and, it seems to me that none of them offer a full explanation – none of them make full sense.

The German Lutheran theologian, Jurgen Moltman spent much of the war in a prison camp, having surrendered to the first British soldier he met, in order to escape fighting for the Nazi cause. The suffering in the POW camps, along with an awareness of the terrible suffering happening in the Nazi concentration camps changed the course of Moltman’s life. Previously without any religious inclination, Moltman went on to become a Lutheran Pastor and academic theologian – he continues this to this day.

Following the theology of Martin Luther, Moltman describes the events of Good Friday as ‘the death of God’: God died on the cross in the form of Jesus Christ. ‘If God cannot experience human suffering and abandonment, how may God ever love humanity?’ At the heart of Chrisitanity, therefore, is God who has died – this is a very radical idea in comparison to the more frequent image of a remote, unchanging and glorious God, distant from human suffering.

So, whenever we suffer, we may think of Jesus Christ crucified on the cross and know that whatever horror we experience, Jesus the son of God has also experienced it too in his crucifixion; and whenever we experience suffering, we may remember that Jesus is there with us, asking the same question “Where is God?” in our suffering.

Moltman draws on the writings of Holocuast survivor, Ellie Wiesel to give us profound example of this:

‘The SS hanged two Jewish men and a youth in front of the whole camp. The men died quickly, but the death throes of the youth lasted for half an hour. ‘Where is God? Where is he?’ someone asked behind me. As the youth still hung in torment in the noose after a long time, I heard the man call again, ‘Where is God now?’ And I heard a voice in myself answer: ‘Where is he? He is here. He is hanging there on the gallows . . .’

There are many questions still to be answered in Moltman’s theology, but his is a compassionate understanding of Jesus’ death, and one tied to human suffering. Moltman writes of a God who profoundly shares in human suffering, not of a God who metaphorically pats you on the back and tells you everything is OK.

Hans Urs von Balthasar was a Swiss theologian and Roman Catholic Priest. He spent many years contemplating the meaning of Passiontide and Easter with his friend, Adrienne von Speyr, who had a series of mystical experiences of the Passion. The outcome of their collaboration was an understanding of the Passion centered on the Holy Trinity. For Balthasar and Speyr, the crucifixion and descent into hell brought the relationship between God the Father and God the Son (Jesus) to a place where the ties were almost broken: it was the Spirit who maintained the most delicate and flimsy of thread between Father and Son, that prevented the annihilation of this relationship of love, and the implosion of the Holy Trinity which is the very nature of God.

To me this speaks of the interior, mental sufferings of many humans. Many people who have suffered from mental illness will know what the disintegration of ‘the self’ feels like. This is happening all around us as one in four people experience a mental health problem each year in England with one in six people report experiencing anxiety or depression in any given week. Mental disintegration or suffering is often treated with contempt and its victims with unkindness. The theology of von Balthazar and von Speyr challenges these attitudes by placing this internal disintegration at the heart of God.

It is always worth pondering the events of Passiontide with an eye on human suffering. It’s not simply about what Jesus’ death and resurrection save us from, but also about what these events share with us. Somehow, in a way we don’t fully understand, the suffering of Jesus envelops the suffering of the world and humanity in compassion and in love. Passiontide therefore becomes a time for us to exercise compassion towards suffering humanity, and to reach out in love in whatever way we can.

Amen

Tweet