A few years ago, I dealt with a situation in a Vicarage in Burnley, where visitors complained of seeing a shadowy woman in a vintage dress who emitted a feeling of intense sadness. We did a bit of research to find out who this woman might be. We stumbled upon the story of a Vicarage family from the middle of the 19th century. In two particular years in the mid 1850s, the Vicar had conducted the funerals of over 1000 children each year. Five of these were his own children. We said a requiem for the Vicar, his wife and his children, and the shadowy woman disappeared – the Vicarage has been peaceful since.

But the astounding rates of child mortality have stayed with me ever since. In the case of the parish in Burnley, the deaths were associated with accidents in the cotton mills, poor nutrition because of extreme poverty, and of course with disease – typhus, smallpox, scarlet fever and cholera, all of which thrived in overcrowded and unsanitary living conditions.

Things weren’t so different in Jesus’ day, when 60% of children didn’t reach their 16th birthday. Children were always the first to suffer from famine, war, disease and becoming refugees. Children who did survive would be lucky indeed to do so with two living parents; it’s not hard to see why Jesus used orphans (along with widows) in his teaching as the ultimate image of vulnerability.

Children occupied a strange place in society – they were loved not least because they represented the succession or continuation of family life. But they were not esteemed as modern children are in our own culture – although no doubt loved, children held little status and had no rights. Most wouldn’t have received an education – especially girls.

So when Jesus talks about welcoming a child he really is talking about welcoming the most vulnerable people in society. Children were ephemeral – they could so easily die – and they had no social status. And yet Jesus sets such a child in the midst of his disciples and tells them that to welcome a child is to welcome God. That’s a big claim!

This setting of a child in their midst is Jesus’ way of teaching his disciples about greatness. They’d’ been squabbling amongst themselves about who was the greatest, the most important. He told them that, in God’s kingdom, the greatest are the servants – basically that the most important to God are the least important in the eyes of the world.

This, then, has nothing to do with a sentimental view of children as being innocent and sweet, although children are very endearing when they’re like that. Sadly, we know children can also be cruel and bullying – any teacher will tell you all about this. What it IS about is how we as individual Christians, how we as a local church, and how we as part of the Church of England, see the world around us. We tend to give attention to ‘important’ people. If the Bishop or another VIP is coming to see us we make sure the church is extra clean and we buy posh biscuits. We all do it: we have our radar attuned to powerful, influential or wealthy people. I suppose this is natural – these people have the capacity to shape our lives, for good, or for ill.

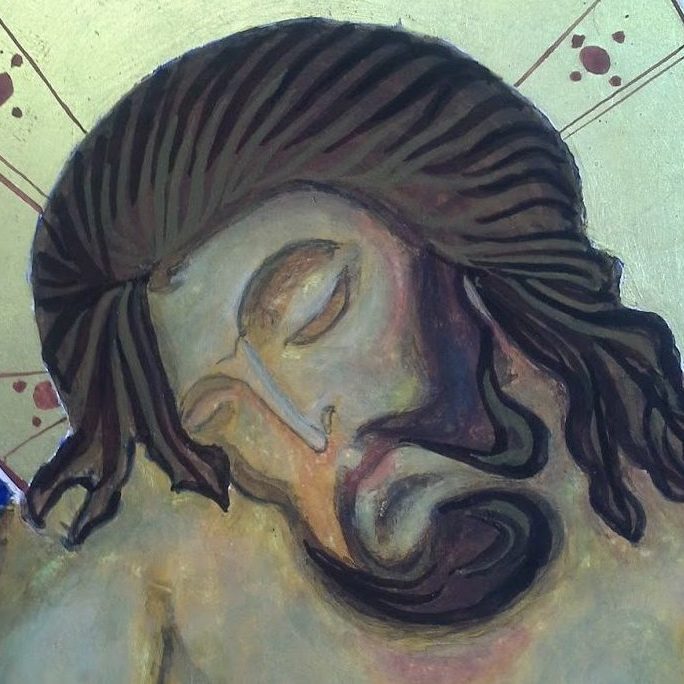

Jesus invites us to see things differently. He asks us to tune in to a different wavelength; the people he asks us to value most highly are those whom we tend not to notice, almost as if they are transparent like a very fine piece of cloth. Or perhaps people we deliberately avoid seeing because they make us feel uncomfortable. Or, quite simply, those who are most vulnerable of all, those who grasp on life itself is tentative, fragile. When we welcome such as these, we welcome Jesus, we welcome God. When we turn such people away, we turn away Jesus, we turn away God.

Because Jesus gives the example of a child as one who is to be welcomed, he addresses the disciples’ quarrel about who is the greatest, the most important. It is the same pattern of turning the status quo upside down. The greatest are those who serve. There is nothing here about success, wealth or even popularity.

By implication, this passage of scripture also tells us who we should serve. Jesus isn’t asking us to serve the rich and powerful and make an extra special fuss over them – although we will probably continue to do this as it’s impolite not to. Jesus is asking us to serve vulnerable and fragile people. We know this: this is the history of the church in tending the sick and caring for the vulnerable. Familiar though it may be, this is something we have to remind ourselves of regularly. We need to adjust our eyes to see people who go unnoticed – it’s easy to see our friends and families, and to look after them. But if we turn our heads a little further, there are others there, waiting to be told that they are God’s precious ones, although the world out there ignores, even despises them.

Tweet