Easter 3. 2023

If you were taking part in a sort of ‘Desert Island Discs’, where, instead of choosing music, you were choosing bits of the bible, which bits would you choose? I suspect many might take Psalm 23, maybe the story of Jesus’ birth from Luke’s Gospel, and perhaps this passage – the Road to Emmaus. Personally, I would add, amongst others, John’s account of the first Easter morning – ‘Early on the first day of the week, while it was still dark’, Psalm 139 – ‘O Lord you have searched me out and known me’, the story of Jacob wrestling with God from Genesis, and the Valley of the Dry Bones returning to life, from the prophet Ezekiel.

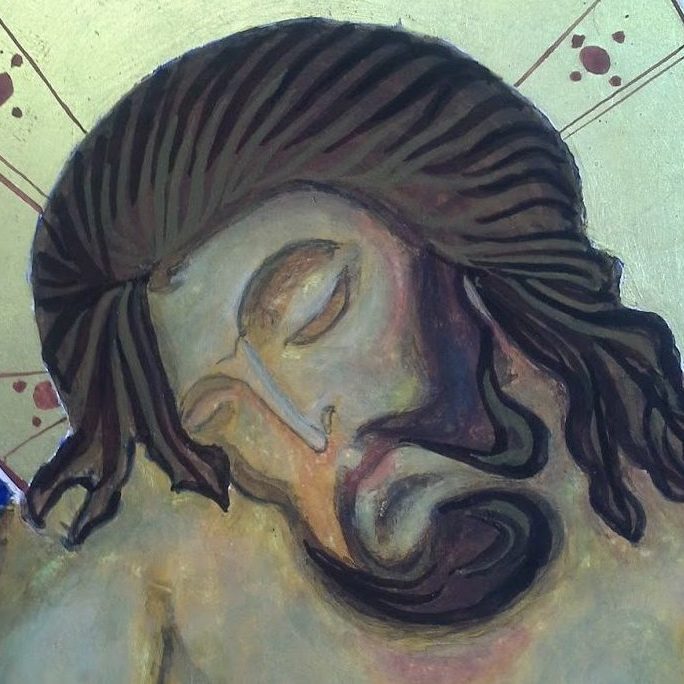

Today, we are blessed to have read the account of the road to Emmaus; one of the most profound and beautiful of the Gospel stories. We can imagine, with some vividness, the hearts of the two disciples lurching then leaping, when they suddenly recognise that it is Jesus who has walked with them on the road, when he blesses and breaks the bread.

We still do the same thing each week – we bless and break bread, and share the bread and wine, knowing that, as we do this, seen or unseen, Jesus is here with us. The breaking of the bread is really the central act of the Eucharist – a moment to raise your eyes from the service sheet and look up to see, understand, that in this action, Jesus is with us: to understand that incomprehensible truth that he is risen. As we witness the breaking of the bread, we count ourselves as fellow travellers and witnesses with those disciples on the Emmaus Road all those years ago. We’re part of the ongoing story that reaches beyond the pages of the Bible into our own time and our own place. In the breaking of the bread, Jesus is with us – the risen one, our familiar teacher and friend. Our Saviour.

Our familiar friend – this is true. But in this wonderful story we see another truth: another example of the uncatchability of Jesus. He said to Mary Magdalene, the first witness to the resurrection, ‘do not hold on to me’, and we can see the same here. Once the two travellers have recognised Jesus, he is gone. They can’t catch hold of him, they can’t keep him, they can’t put him in a box – he is gone.

The same is true for us in two senses:

First, our God often seems absent. Sometimes it is as if we too are looking at an empty tomb: or that we arrive just after Jesus has left – he always seems tantalisingly just ahead of us, just moved on – and we can spend a lifetime looking, searching – like Baboushka, whose legend tells of a woman who spent a lifetime looking for the infant Christ.

This absence, at the heart of our faith, is the reason for Christianity’s great potential for subtlety and openness. At its best, Christianity has accepted that faith is a journey, not of seven miles, but of a lifetime – something that always challenges and renews, something that has endless possibilities, and that can endure even through great uncertainty and change. Those words again ‘He is not here, he is risen, which we hear each Easter, express this great anomaly at the heart of our faith – the triumph and the mystery held within one sentence.

Secondly, Jesus – God – is always beyond our grasp. God is not comprehensible, catchable, tameable. We used to express God’s ‘otherness’ in terms of God’s anger and judgement. Now we speak less of these things, and perhaps rightly so, as the threat of GOd’s wrath has undoubtedly been used to terrify people into submission and obedience. I think it is still possible to locate the otherness of God within the focus on God’s love: love requires openness, founded on a belief in God’s love for all God’s children and for the creation which God saw was ‘very good’ – in meeting others, strangers, ‘the other’, in the creation around us, we come to know that God is vast beyond measure, beyond our knowing, bigger than our imagining. We cannot truly hold God’s entirety in our hearts: we see and understand only in part. We need to beware of building a God in our own image – small enough for us to tame, tame enough to be safe, safe enough not to be God at all.

Two events yesterday are examples of things that can stretch our minds to comprehend more of God: yesterday was both Earth Day and Eid. Particularly in Blackburn where almost half of the population is Muslim, there is plenty of space (and need) for us to find God worshipped in a different way, by different people. That doesn’t, in my opinion, mean either surrendering our faith or trying to convert Muslims to ours – there is surely a space for mutual respect, for listening, even for admiration – here is something that can broaden our understanding of God..

Earth Day saw huge crowds, including many Christian groups, marching through London to protest that action be taken on climate change. If we think about our focus on God’s love, we very quickly get to the impact of climate change on all sorts of people, but especially the poorest and most vulnerable people in the world who have the fewest resources to protect themselves – once again we are transported from our relatively comfortable lives, into the circle of God’s love, compassion and justice.

A focus on God’s love drives us, as at Emmaus, to encounter God in the face of a stranger. This is never easy for us. We are always more comfortable with people who are like we are. But it is essential for us, nonetheless, for us to open our eyes and our hearts, and to look for Jesus Christ in the faces of strangers. I think, now, the future of our planet depends on it, both in terms of tackling the climate crisis, but also to prevent a descent into war and violence.

I finish with a beautiful story from Jewish teaching;

The rabbi asks his students: ‘How can we determine the hour of dawn, when the night ends and the day begins?’

One of his students suggested: ‘When from a distance you can distinguish between a dog and a sheep.’

‘No,’ was the answer of the rabbi.

‘Is it when one can distinguish between a fig tree and a

grapevine?’ asked a second student.

‘No,’ said the rabbi.

‘Please tell us the answer then,’ said the students.

‘It is, then,’ said the wise teacher, ‘when you can look into the face of human beings and you have enough light to recognise them as your brothers and sisters. Up until then it is night, and darkness is still with us.’

From today’s Gospel: Then their eyes were opened, and they recognized him.

Amen

Tweet