Today’s gospel reading carries a most appalling story: the story of a poor woman whose husband dies and who is obliged to marry, one after the other, his six remaining brothers who also die, one after the other. Despite the seven husbands, the woman bears no child. Then she too dies. The people who told this story showed no interest in this poor woman’s life, but were interested only in the theoretical question of which of her seven husbands she will be married to in heaven – a heaven the people concerned didn’t even believe in. We have to remember that this is only a story – a story made up by the Sadducees in an attempt to trap or trick Jesus into giving the wrong answer to an impossible question about heaven.

But behind this story of the made up woman hides the story of many, many women in the time of Jesus. The word ‘widow’ connotes one who is silent: women did not speak in public life, and if a woman had no husband to speak on her behalf she had no recourse to justice or help. This was worse if she had no son – as this was the case for the widow in this terrible story. This is a fictitious story of an extremely vulnerable woman, but any real woman with no husband and no son would have been extremely vulnerable.

I have serious objections to such a woman being used by the learned men of the day to try to score theological points. It’s almost like the intellectual equivalent of a sick joke. This is theology at its worst – petty arguments which use and abuse people, setting aside the humanity and compassion which any decent person would feel about such and woman, such a story, taking away her humanity and turning her into the victim of a petty argument in which clever men bolstered their egos and vied to show how clever they were. Theology at its worst. Sadly, it still happens. I remember being at General Synod during the discussions about the ordination of women – there was often the same tone: as if women were a theory rather than real flesh and blood. The current debates about homosexuality have the same flavour: it’s all about shoring up pure theology and not about the lives of real people. Not until the objects of theological discussion are recognised as real people, flesh and blood, or better still, known and loved, do those discussions have either validity or truth.

InJesus’ time, and up until a few hundred years ago, women’s lot was largely to do with having children, especially male children – this continued the family name and the family line. This was especially important for the Sadducees’ world because they didn’t believe in resurrection, in life after death. To them, you lived on through your children and grandchildren – this was your only hope. This is still a very prevalent view in todays’ world – many do not believe in heaven or an aferlife, and believe that they will live on through their children and through the difference you made to the world and in the memories of friends and family.

Jesus is offering something better: he says there will be another life after this one – in it we will be like angels, we will be children of God, children of the resurrection. It will be a very different life to this one – for a start off, Jesus says there won’t be marriage: heaven, in other words, isn’t going to be like here. In many ways, that’s hard to bear: at its best, marriage brings purpose, deep companionship (spouse, children, grandchildren), abiding love, pleasure, happiness, joy, contentment, all manner of blessings. Of course, even the best of marriages aren’t perfect – there will be disappointments, arguments, bad behaviour. As we know many marriages don’t last, many are unhappy, and, as I have recently experienced, even marriages that do last come to an end when one half of the couple dies.

But think of the very best marriage with the deepest, truest and most abiding love. When Jesus talks of our resurrection, he is not offering something less than this – he’s not offering us a second best or a poor substitute. For us to be angels, to be God’s children in God’s presence, then all of life, all relationships, must be better than the most profound love we experience on earth, and this love will last forever – it will not end in breakdown, it will not end in death, there won’t be bad days – it is eternal love and it is eternally beautiful love.

In this Kingdom season, we take an initial look at some of the great themes of advent, traditionally Death, Judgement, Heaven and Hell. Even saying them makes you squirm, doesn’t it? It is very easy for us to become earthbound – we talk about resurrection in our services, in our funeral service we always talk about death not being the end, about death being swallowed up in victory, but we don’t really engage with ideas of heaven – let alone hell. I think we’re inclined to pretend that death doesn’t really happen until we have no alternative but to face reality, and even when someone has died we struggle to believe it’s true. If we were better believers in Jesus’ promises, we would take death in our stride and truly see it as the gateway to eternal life. But we focus so much on the here and now that we forget Jesus’ promise of something beautiful. Today let us remember that: we will be like angels, children of God, children of the resurrection.

This is the destination of this life – and it is this hope that stirs us to make this life better. Instead of projecting this life onto the next, which leads to a rather insipid and sentimental viewof heaven, perhaps we can project the next life onto this one, working always to fill this world with love, compassion, learning to see God’s beauty, learning to spot the angels amongst us – we have a few here, I think, and learning to value eternal things, rather than seeking after temporary satisfactions. And although this life can never be quite like heaven, we have a template, we have an idea of what is important and we have hope. This is what God’s Kingdom is about – finding heaven here, building heaven here, living Jesus’ Kingdom parables now.

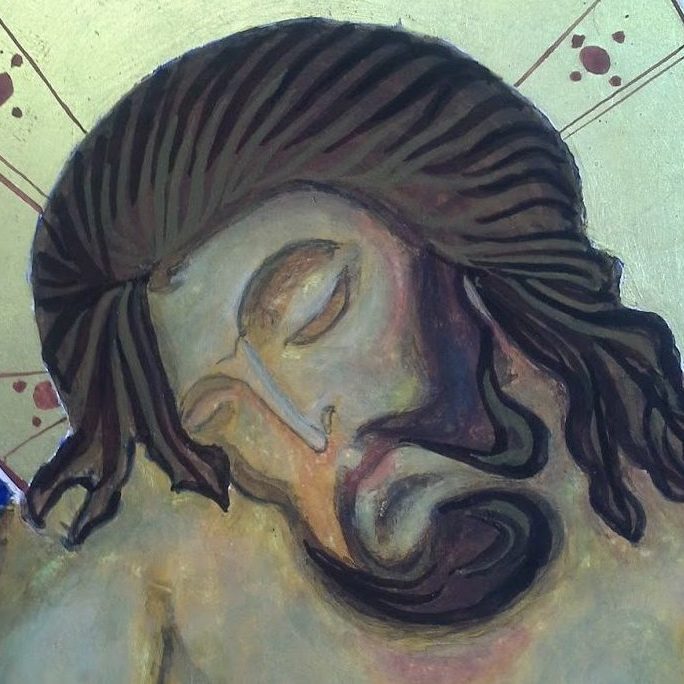

And in the middle, between this life and the next, we find the Crucified One who takes away the sin of the world. That is why we need to come, very often, to stand at the foot of the cross where our failures, hurts and disasters are caressed into wholeness – are redeemed, in Jesus’ gentle hands. Think about those hands – the hands of God, carrying the scars of nails – the hands that embrace us at the end of this life and welcome us into the next. These hands are our hope of redemption. These are the hands that will reach out to welcome us home.

Tweet