I have a copy of a most remarkable book called ‘If you sit very still’ It’s by a woman called Marian Partington who’s sister Lucy disappeared one night on her way home in December 1973. What had happened to Lucy remained a mystery for almost 20 years until her remains were found in the cellar of a house inhabited by Fred and Rosemary West. She was still wearing the gag that had kept her silent in her last minutes of life.

Marian Partington is a Christian – a Quaker. She describes her journey of forgiveness from murderous rage aimed at the whole world outside herself – to a place of compassion where she has come to care deeply about Rosemary West – that she will not spend the rest of her life in a state of self delusion and self ignorance. The turning point for Marion came when she recognised that the enormous rage which she discovered within herself could have lead her down a similar road to the Wests, had her upbringing and circumstances been different. The Wests inflicted on Marian’s sister Lucy the things that had happened to them as children – they were repeating a pattern of abuse.

Desmond Tutu, who developed tools for forgiveness when he was the chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa in the years following the end of apartheid, observed that to forgive is not just to be altruistic: it is the best form of self-interest. It is also a process that does not exclude hatred and anger. He said ‘The only way to experience healing and peace is to forgive. Until we can forgive, we remain locked in our pain and locked out of the possibility of experiencing healing and freedom, locked out of the possibility of being at peace.’

I remember seeing Winnie Johnson, the mother of Keith Bennet on TV years ago. Keith was 12 when he was kidnapped and murdered by Ian Brady and Myra Hindley. This TV interview has stayed in my mind over the years because of its utter tragedy. She seemed to be completely consumed by anger and hatred and pain and found it impossible to forgive, which isn’t really surprising – who knows how we would be in such a situation. In fact Keith’s family specifically refused to forgive or forget. Winnie Johnson died in 2012 without ever knowing where her son was buried. I think she did move on from the hatred which consumed her, but at the time of the interview you could see it spreading and tainting her family – a terrible legacy.

I have used extreme examples: I suppose these help us to bring the issue into focus. Thankfully, most of us will not have such traumatic and difficult things to forgive: for most people, forgiveness is much less profound. But it is something our faith requires of us, and with its roots in the passage in today’s gospel and other similar teachings of Jesus.

Forgiveness is a strange thing. Some people seem to be able to forgive easily, others hold on to their pain and bitterness for years – sometimes over the pettiest things, sometimes over things which have devastated lives and relationships. A colleague was telling me that they had recently been requested to conduct two funeral services for someone, as the family had fallen out and couldn’t bear to be in church at the same time. Another had been asked to conduct the last rites twice so they could be observed by two warring factions of one family. It is almost, sometimes, as if lack of forgiveness develops a life of its own, like a cancer that grows and grows; like a parasite that feeds off its host, sapping energy and strength, until it destroys its source of life, at which point we hope it, too dies – although I suspect it has the capability and transferring itself to someone else. I think the original fallout is often quite trivial – the subsequent grudge grows out of all proportion.

Today’s gospel tells us that we must forgive time and time again, because that is how God is with us. This is a story full of hyperbole – it’s an exaggerated story told to make a much simpler point. So we mustn’t think that God is a tyrannical king ready to throw us into prison for our debts or sins: that’s not what the story is about. What it IS about is that God forgives and we are called to do likewise.

Now this is sometimes a tall order. Forgiveness is something we wrestle with and are confused about. I’d like to tell you some things that forgiveness isn’t:

Forgiveness isn’t the same as allowing bad things to continue – you can challenge abuse, injustice, unfairness, and still forgive. Nor is it condoning bad behaviour.

Forgiveness isn’t about forgetting – indeed remembering is part of forgiveness.

Similarly, forgiveness isn’t about denying pain – acknowledging and owning the pain caused is part of forgiveness.

Forgiveness isn’t about trusting – you can forgive but be wise in how much the person you have forgiven is given access to your life.

Forgiveness isn’t passive – it is an active choice.

I could go on. There’s lots of stuff online about this – just google ‘what forgiveness isn’t.

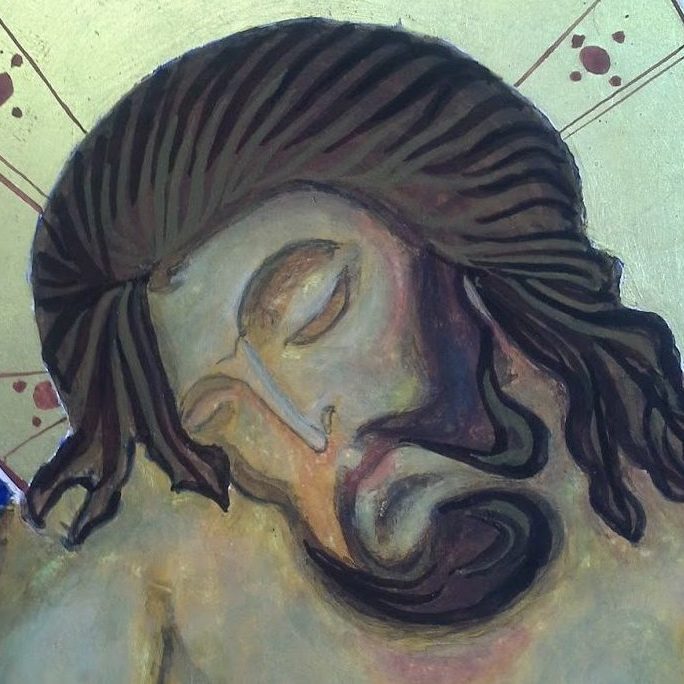

I think forgiving someone is refusing to allow them to have power over you – it is a kind of detachment. It is also about trying to see the world through God’s eyes. I’m taken back to some medieval carvings I saw in the Catharijneconvent in Utrecht earlier this year: a set of half lifesize wooden and painted figures of the slumbering disciples in Gethsemane: they were supposed to be awake and supporting Jesus in his time of anguish, but they couldn’t keep their eyes open despite him rousing them on several occasions. They really let him down. Looking at them was a most profound experience, because they are depicted with such love – you wanted to say out loud ‘Oh, aren’t they just lovely’. And that, of course, is how God sees us. To God, we are just lovely. Annoyingly, it is also how God sees people we don’t like, people who have harmed us, people who are badly behaved and rude – and people who have done evil.

You can see, when you look at it this way, how much pain evil deeds cause to God – because the people who do evil are actually God’s beloved. That is not to say that evil has gone unnoticed, and it is not to say that evil will not be held to account – as in forgiveness, the action and the perpetrator are two different things.

For me, forgiveness is a struggle. I find myself praying ‘Help me to want to forgive.’ I think that’s OK, because it is an engagement, rather than simply allowing things to fester.

It is also about forgiving myself: Someone said ‘It is easier than one thinks to hate oneself. Grace means forgetting oneself. But if all pride were dead in us, the grace of graces would be to love oneself humbly, as one would any of the suffering members of Jesus Christ.’

That word, ‘humbly’ – humility – has much to do with forgiveness too, for which of us hasn’t acted wrongly, caused hurt or behaved selfishly – we who are so lovely, in God’s eyes. To acknowledge this takes us from the high horse – the vantage point from which we judge without mercy.

In forgiving, may we be humble and grace filled, but also strong and determined. Amen

Tweet